Make that make sense. – Former Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

After 2 years of exceptional performance, U.S. equity markets backtracked to start 2025. Investor optimism quickly deteriorated after Trump’s inauguration, unable to shake off repeated and often inflammatory statements about remaking the nature of global trade.

After 2 years of exceptional performance, U.S. equity markets backtracked to start 2025. Investor optimism quickly deteriorated after Trump’s inauguration, unable to shake off repeated and often inflammatory statements about remaking the nature of global trade.

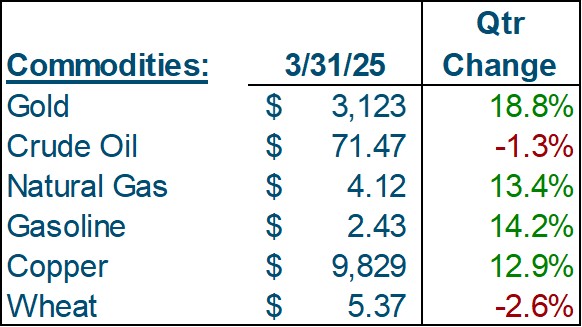

Confronted with the reality that the U.S. will attempt to forcefully rewrite the terms of trade with all its trading partners, whether friend or foe, investors must re-assess their expectations for economic growth, the labor market, consumer spending, inflation, interest rates and corporate profits. And though we ourselves have highlighted the risks of anti-trade policies in each of our last two Reviews, retail investors in particular are buckling under the constantly negative and often sensationalist headlines that have become the go-to tactic among popular news and social media outlets. The truth, as is often the case, is more nuanced.

The U.S. faces disproportionately high trade barriers to its exports, an asymmetry compounded by the fact that, as the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar is systematically stronger than it otherwise would be, which makes U.S. exports more expensive in foreign markets and foreign imports less expensive in the U.S. market. These two factors fuel an ever-widening trade deficit with the rest of the world, which has hollowed out (in Trump’s opinion) the U.S. manufacturing base, creating an intolerable reliance on imports critical to the country’s national security(such as electronics and steel). Thus, there is an intrinsic connection between global trade and the national security interests of the U.S.

Previous attempts to rectify the country’s trade deficits have proven futile unless tariffs were included as part of the solution. We continue to hope that Trump’s strategies, which rely heavily on tariffs, will be used as negotiating leverage designed to ultimately reduce the trade barriers U.S. exporters face. But clarity on this front is limited, and as such, we remain cautiously optimistic, aware of the deleterious effects of tit-for-tat tariffs, but optimistic that his tactics will bring our trading partners to the table in a way that ultimately results in fairer trade.

The Global Economy

In lieu of our typical assessment of the global and U.S. economies, we thought it would be more valuable to dive into the esoteric world of global trade and look at its current state from the U.S. perspective, consider a number of options that can be used to address the lack of balance, and then, with that context, describe how we see Trump’s efforts and what they could mean for the global economy, the U.S. economy, and global financial markets going forward. This is going to get a bit technical, but we’ll do our best to make it interesting.

In lieu of our typical assessment of the global and U.S. economies, we thought it would be more valuable to dive into the esoteric world of global trade and look at its current state from the U.S. perspective, consider a number of options that can be used to address the lack of balance, and then, with that context, describe how we see Trump’s efforts and what they could mean for the global economy, the U.S. economy, and global financial markets going forward. This is going to get a bit technical, but we’ll do our best to make it interesting.

Understanding Trump’s intentions begins with understanding the current state of global trade. Trade is ultimately about two conflicting goals; 1) maximizing global wealth by maximizing global resource utilization efficiency, and 2) maximizing a single nation’s wealth. Economists have long understood the concept of comparative advantage, whereby certain nations have intrinsic economic efficiencies and advantages compared to other nations based on their resources, and that because of comparative advantage, global wealth maximization is accomplished through frictionless trade.

In this framework, people and money are entirely free to move wherever they can produce the greatest value and are rewarded most when they are able to sell those goods and services without barriers. Finite resources are utilized most efficiently, prices paid are as low as possible, and the world’s population as a whole is as wealthy as it possibly can be. Many countries recognize this altruistic goal and pursue it to some degree, including the U.S., which has largely taken this position since the Washington Consensus was adopted in the 1980’s.

Contrary to that goal, however, is the desire to maximize a nation’s wealth, which intrinsically introduces inter-national competition into the global trade order. Nations rightfully prioritize their own labor pool and resources in order to maximize their own national wealth. Hence, global trade is, in reality, a convoluted web of competitive efforts designed to extend comparative advantage and enhance a nation’s competitive position vis a vis other nations.

This web is woven using barriers such as tariffs, state-provided subsidies for domestic companies, taxes, and laws and regulations designed to disadvantage foreign competitors. Every country uses a combination of these to suit its own comparative strengths and weaknesses. Theoretically, global institutions such as the World Trade Organization police the unfair application of trade barriers, but any intellectually honest observer must admit that its ability (or perhaps even its willingness) to enforce fair trade is a myth.

Given the opaque and complicated nature of trade barriers, assessing a country’s free trade posture is difficult, but generally speaking, the U.S. ranks among the most generous when it comes to granting foreign access to its market. While this posture undoubtedly benefits the U.S. consumer, it also represents an asymmetrical structure that disadvantages U.S. companies, labor, and investors. The end result is a trade imbalance, whereby the U.S. buys more stuff from other nations (imports) than it sells to other nations (exports), and since net cash flow with other nations is negative, the U.S. must borrow money from other nations to fund those purchases.

In theory, trade imbalances over time are rectified through the currency exchange rate mechanism. When a country runs a trade surplus over time, its currency generally strengthens relative to those of its trading partners who are running trade deficits with it; This currency adjustment makes the trade surplus country’s exports more expensive, all else equal, and imports from its trading partners less expensive, both of which act as a counter-weight to limit further trade surpluses, potentially even reversing the trade surplus to a deficit.

In the case of the U.S., persistent trade deficits do not result in a weaker dollar because the U.S. dollar serves as the world’s reserve currency, used in 60% of global trade. This systematic demand for U.S. dollars, which grows as global trade grows, keeps the dollar elevated compared to other currencies, preventing the normal exchange rate clearing mechanism from improving the U.S. trade deficit.

Being the world’s reserve currency has important political benefits, the main one being the ability to impose our will on the rest of the world using the financial system rather than through the use of kinetic military action (bombs and bullets). The ability to use economic sanctions and other financial-system related methods are a privilege the U.S. enjoys and wants to maintain. With that said, in Trump’s view, the systemic trade deficit that the U.S. runs with the rest of the world weakens the U.S. economy and robs its labor market and investors of their fair share of compensation and contributes to the inexorable rise of national debt, all of which represent a clear and present danger to the long-term stability and security of the U.S.

A persistent trade deficit can be rectified with a unilateral or multilateral effort to weaken the currency of the country with the trade deficit. This tactic was employed by Ronald Reagan in the mid 1980’s. A few years prior to his election, an exogenous shock (the Arab oil embargo) created very high inflation, and after a few years of failed attempts to curtail it, newly appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker raised the Fed’s benchmark interest rate to nearly 20% and kept it there to “break the back” of inflation. High interest rates depressed economic activity, which prompted Congress to lower taxes and increase spending in order to stimulate the economy, which expanded the fiscal budget deficit and created, for the first time since World War II, a persistent trade deficit with the rest of the world.

Notably, although the time frame is shorter and inflation and interest rates didn’t rise to the same levels, the Covid pandemic and subsequent years have largely played out the same; an exogenous shock leads to inflation to which the Federal Reserve responds with higher interest rates, all of which is accompanied by expanded government spending, wider fiscal deficits, and rising debt.

In both cases, interest rates rose and stayed elevated, in part because of the Fed’s actions and in part because of the increased Federal budget deficit. In both cases, the higher interest rates pushed the U.S. dollar up significantly relative to other currencies, and because U.S. products became more expensive in foreign markets, and foreign products became less expensive in the U.S. market, the nation’s trade deficit widened dramatically. In both cases, the presumed culprit creating the trade deficit was the strength of the U.S. dollar.

Which is where the 1985 Plaza Accord comes in. Pressure from domestic manufacturers, especially from the auto manufacturers and heavy equipment makers like (John) Deere, triggered Reagan’s efforts to address the trade deficit. Foreign countries like France and West Germany had been pressing the U.S. to consider taking actions to weaken the U.S. dollar because the strong dollar was creating inflationary pressures outside of the U.S. The Plaza Accord, between the U.S., France, West Germany, the U.K. and Japan, formalized a coordinated effort among the five countries to systematically weaken the U.S. dollar in the currency markets, believing that doing so would reverse the U.S. trade deficit (make U.S. exports less expensive in foreign markets and foreign imports more expensive in the U.S.) and help alleviate inflationary pressures abroad. In 1987, after the U.S. dollar had weakened, the group of five signed the Louvre Accord which effectively brought the multilateral effort to manipulate the U.S. dollar to an end.

In a broad sense, the Plaza Accord accomplished its goals. The U.S. dollar weakened against the other countries’ currencies and the U.S. trade deficit with western Europe declined, at one point returning to a trade surplus. However, the U.S. trade deficit with Japan remained elevated because Japan, unlike western Europe, had already adopted a variety of trade barriers that prevented U.S. goods from penetrating Japan’s domestic market. Ultimately, the weaker U.S. dollar, which depreciated by 50% versus the Japanese yen, had no effect on the U.S. trade deficit with Japan because of Japan’s trade barriers.

We think Trump and his advisors have concluded that, even if a weaker dollar is somewhat desirable, foreign trade barriers are the principal obstacle to rectifying the U.S. trade deficit and are hyper-focused on them. And with good reason; the conclusions regarding foreign trade barriers and their impact on the U.S. trade deficit are quite strong, as evidenced by the divergent trade balance results between western Europe and Japan. The Plaza Accord clearly demonstrates that it’s impossible to affect any improvement in the trade deficit by weakening a country’s currency if foreign countries prevent U.S. goods and services from further penetrating their markets.

Certain countries are more egregious than others when it comes to the utilization of trade barriers; the most egregious perpetrators tend to be emerging market economies such as China and India where domestic companies aren’t yet efficient or sophisticated enough to compete with foreign companies. During his first term, Trump was able to effect policies that curtailed the U.S. trade deficit with China. But since his first term, our trade deficit has expanded with other countries, especially with our closest trading partners with whom the U.S. has some of the least restrictive trade barriers (think Canada and Mexico, where our trade deficit, for example, has more than doubled since 2018).

Which is why we think Trump, during his second term, has ramped up the aggressiveness and widened his targets to include dozens of nations, including many with which the U.S. has comparatively lower trade barriers. In these cases, although the U.S. still trades at a disadvantage because of the asymmetrical nature of each country’s trade barriers, the issue may not solely be about other countries’ trade barriers to U.S. exports. It may also be about the fact that China, for example, in response to Trump’s initial trade restrictions, signed favorable trade deals with the U.S.’ closest trading partners as a way to penetrate their markets and from there, access the U.S. market on those countries’ more favorable trading terms with the U.S. In other words, Trump and many republicans see the U.S.’ closest trading partners as side doors, so to speak, that China and others have successfully exploited to circumvent direct U.S. trade restrictions.

This would take the form, for example, of Chinese made auto parts being sold to Mexican distributors, which then export them to the U.S. Current country of origin standards are not strong or standardized enough to differentiate between auto parts that actually originated in China and made their way into the U.S. through Mexico from those that actually originated in Mexico. The extensive nature of global supply chains, established and reinforced through decades of “free trade”, where components and parts may traverse the globe multiple times before making their way into the U.S., make identifying the ultimate country of origin virtually impossible. We think this is why Trump has, without much fanfare or notice, cited stronger country of origin standards as a key element to any renegotiated trade deal with Canada and Mexico.

Trump’s focus on reciprocal tariffs, even for the U.S.’ closest trading partners, appears to be his opening negotiating move in an effort to bring our trading partners’ trade barriers down. He currently views the global trade structure as Win / Lose for the world and the U.S. respectively and is threatening a Lose / Lose structure if other nations don’t acquiesce to more balanced trade terms. We are hopeful that his efforts are designed to reduce global trade barriers, not just unwind global trade, which is undeniably beneficial for the U.S. and the world.

The constant drum beat of tariffs and higher consumer prices is, understandably, weighing on consumer confidence and small business optimism. Although a recession later this year or in 2026 isn’t yet our base case, the risks of an economic downturn depend on how other countries respond; if negotiations are fruitful and produce lower trade barriers to U.S. exports, economic activity could accelerate, but if negotiations are hostile and resemble what occurred in the 1930’s, all bets for sustained economic growth are off the table.

In the meantime, investors are confronted with the often volatile, contradictory, incomplete, and sometimes reversed statements Trump makes, creating a high degree of confusion, guesswork, and unpredictability. It seems as though Trump and his team are working through the details in real time in full view of the public, and there is no doubt, watching how the sausage is made unnerves investors.

Equities

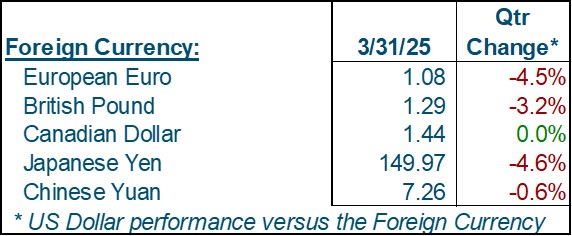

Confusion and unpredictability generally produce heightened risk aversion among investors, which is what transpired in the first quarter. For only the second quarter in the last ten, U.S. equities declined as investors shed many of the same names that carried their portfolios to new heights just one quarter prior, diversifying their holdings into sectors deemed less vulnerable to foreign trade disruptions or into bond-like substitutes.

Confusion and unpredictability generally produce heightened risk aversion among investors, which is what transpired in the first quarter. For only the second quarter in the last ten, U.S. equities declined as investors shed many of the same names that carried their portfolios to new heights just one quarter prior, diversifying their holdings into sectors deemed less vulnerable to foreign trade disruptions or into bond-like substitutes.

If one were to look simply at the headline performance of the major indices, they would miss the deep and widespread pessimism that has taken hold of investors. In fact, it’s hard to convey the extent to which investor sentiment turned negative during the quarter, but the following data points caught our attention: According to Bank of America’s Global Fund Manager Survey, international investors reduced their U.S. allocation by 40% in March, the biggest 1-month decline in the survey’s history; retail investor bearishness hit levels only seen three other times in the last 35 years; internet searches for the term “Recession” now exceed the levels set during the Covid pandemic; and the number of news articles discussing “economic uncertainty” are higher than any other time in the last 30 years other than during the Covid pandemic.

Ironically, history suggests that extreme episodes of investor bearishness (especially retail investor bearishness) are often fruitful opportunities to purchase equities. In this case, however, we fail to see the negative investor sentiment reflected in either earnings estimates or equity valuations, both of which should be declining.

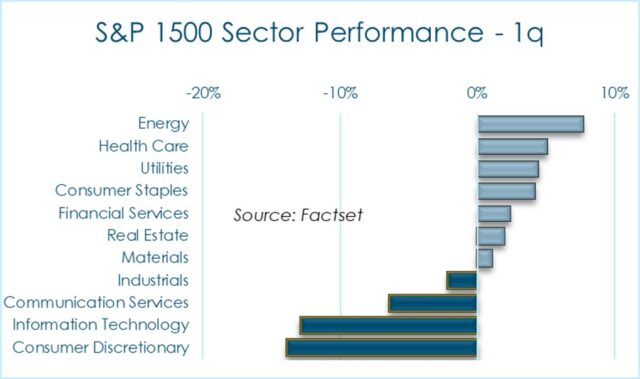

Earnings estimates are set by Wall Street analysts, and, having served as one in the 1990’s, we understand fully the reluctance of analysts to lower their earnings estimates before management teams update their own guidance. In this regard, perhaps it’s not surprising that earnings estimates are not falling. But we would not expect them to be rising, which they are in fact doing.

Earnings estimates are set by Wall Street analysts, and, having served as one in the 1990’s, we understand fully the reluctance of analysts to lower their earnings estimates before management teams update their own guidance. In this regard, perhaps it’s not surprising that earnings estimates are not falling. But we would not expect them to be rising, which they are in fact doing.

In March, analysts raised their 2025 and 2026 earnings estimates 14% and 11% respectively and currently expect U.S. equities to deliver nearly 15% earnings growth in 2025 versus 2024 and another 11% in 2026 versus 2025. We are skeptical these estimates are achievable, especially if higher input costs resulting from tariffs impair profit margins.

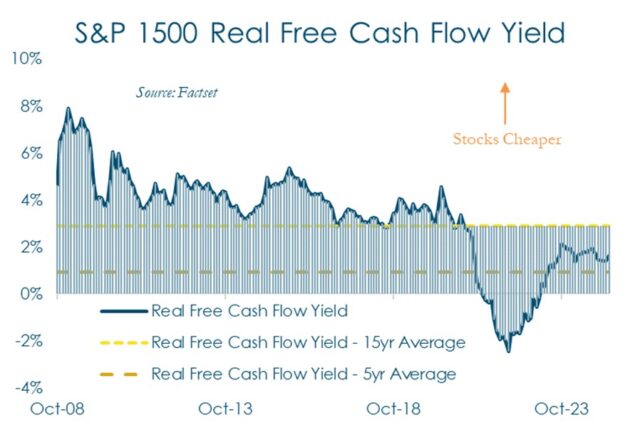

Moreover, equity valuations do not demonstrate a higher degree of pessimism; they are roughly the same as they were at the beginning of the year, and though stocks are less expensive than they have been over the last five years on average, they are still more expensive than they have been over the last 10 and 15 years on average. All of which leads us to believe that as companies report their first quarter results, they may take the opportunity to issue cautious forward-looking guidance, and if they do, equity prices are vulnerable to additional downside movements. As a result, we believe near-term caution is warranted when it comes to the equity markets.

Fixed Income

Fixed income investors are transparently bearish, expecting the U.S. to not only enter a recession at some point in the next 1 – 3 years, but also for inflation to accelerate over the next five years, a phenomenon known as “stagflation”. We aren’t quite that pessimistic, we think the U.S. economy’s strength can handle some trade-related disruption, and that the inflationary shock will be material but temporary, as retailers and consumers adjust to the new reality of inbound tariffs.

Fixed income investors are transparently bearish, expecting the U.S. to not only enter a recession at some point in the next 1 – 3 years, but also for inflation to accelerate over the next five years, a phenomenon known as “stagflation”. We aren’t quite that pessimistic, we think the U.S. economy’s strength can handle some trade-related disruption, and that the inflationary shock will be material but temporary, as retailers and consumers adjust to the new reality of inbound tariffs.

With that said, yields on five-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS, suggest that bond investors estimate the U.S. economy will grow on average about 1.3% over the next five years, while experiencing inflation around 2.6%. This compares to an estimated five-year growth rate of 2% at the beginning of the year and an estimated five-year inflation rate of 2.4% at the beginning of the year. We would also note that yield spreads on corporate bonds trickled up during the quarter, another indication that bond investors are increasingly nervous about a recession.

Commodities

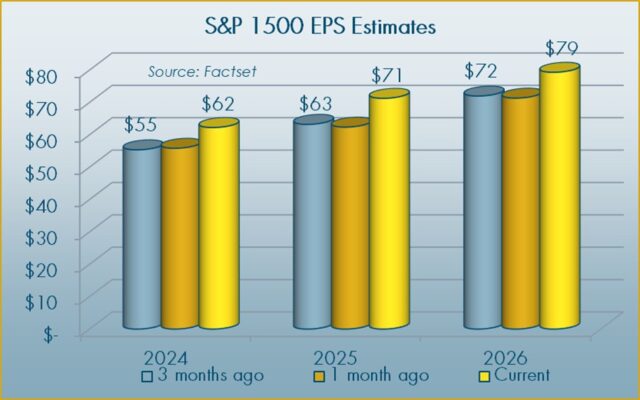

When uncertainty and confusion rise, investors often seek gold as a safe haven and that’s exactly what they did in the first quarter. Confronted with the prospects of a weaker U.S. dollar, potentially risky equities, and higher inflation which erodes bond income, it’s not hard to understand gold’s appeal, which surpassed the $3,000 mark for the first time ever. Oil prices continue to suffer from a rising global oversupply, but domestically, gasoline prices were strong due to refining capacity limitations.

When uncertainty and confusion rise, investors often seek gold as a safe haven and that’s exactly what they did in the first quarter. Confronted with the prospects of a weaker U.S. dollar, potentially risky equities, and higher inflation which erodes bond income, it’s not hard to understand gold’s appeal, which surpassed the $3,000 mark for the first time ever. Oil prices continue to suffer from a rising global oversupply, but domestically, gasoline prices were strong due to refining capacity limitations.

Conclusion

Make this make sense. For most observers, in the U.S. and around the world, the dramatic antagonistic shift in U.S. policy towards its neighbors and trading partners is incomprehensible. We think the key to making it make sense lies in part within the paper Dr. Stephen Miran penned in November after Trump was elected. Titled “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, Dr. Miran, who now serves as Chairman of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, cohesively ties U.S. trade policy to U.S. national and global security interests in light of the current global trading framework.

He cites the U.S.’ role as the world’s reserve currency and its burdens while at the same time admitting that being the world’s reserve currency has benefits, chiefly that it simultaneously makes the U.S. the world’s primary superpower. But as a liberal democracy superpower, these benefits also accrue to U.S. allies, and because of that, some degree of burden sharing is reasonable. He argues that, as the global trading system is currently structured, with asymmetrical trade barriers that reflect the U.S.’ generosity after World War II, the costs associated with being the world’s reserve currency fall unfairly on American companies, their employees, and U.S. taxpayers. He further argues that the global trading system as it is currently structured is partly responsible for generating persistent U.S. trade deficits which have contributed to the deterioration in the U.S. industrial base and with it, the country’s ability to rapidly produce the materials and components necessary should a prolonged kinetic confrontation with China materialize.

He advocates for a restructuring of U.S. trade policy, one in which the economic burden of being the world’s reserve currency is shared more fairly among U.S. allies and trading partners, while at the same time, supporting the U.S. industrial base, both of which would preserve the U.S.’ role as reserve currency and liberal democracy superpower. This is his essential argument; that economic power, which is in part dependent on a strong domestic industrial base, is inextricably linked to military power, and that the current international trade framework is slowly eroding the U.S. industrial base and its economic and military power, to the detriment of liberal democracy around the world. This is both a trade policy and a domestic industrial policy, all designed to support liberal democracy’s status as a world superpower.

Accomplishing this “burden sharing” may eventually include weakening the dollar, but doing so while trade barriers are in place will have no impact on the trade deficit or the domestic manufacturing base, as evidenced by the experience from The Plaza Accord. Tariffs therefore are leverage to open markets for domestic manufacturers, reduce the trade deficit, and strengthen the domestic industrial base, which at present, would not be able to produce a number of essential materials or components necessary to manufacture advanced military weapons.

Having the benefit (or curse) of still writing this piece on “Liberation Day”, on which the president quantified his reciprocal tariff list, it’s clear to see the logic behind the plan. By reciprocating against countries with the highest barriers to U.S. exports with relatively high tariffs, but keeping a low, 10% tariff rate for countries that have the lowest barriers to U.S. exports, he is clearly inviting the worst offenders to come to the negotiating table with the goal of reducing bilateral trade barriers with that country. It also explains why he implemented a universal 10% tariff, which he likely sees as a fair way to share the economic burden of the U.S. being the world’s reserve currency with the rest of the world.

At the same time, as an end-around foreign governments, he is encouraging foreign companies that would otherwise face high export tariffs to the U.S. to sidestep those entirely by investing directly in the U.S. It offers the stick and the carrot to foreign governments, but ultimately puts the decision-making power in the hands of companies if they happen to domicile in a country that opts not to reduce its own trade barriers to the U.S.

He is pursuing a singular goal by way of two avenues; to accelerate economic growth by 1) reducing trade barriers to U.S. exports in order to create more opportunity for American companies, their employees and their investors, and 2) inviting foreign direct investment from foreign companies which in turn creates more jobs for American citizens and rebuilds the American industrial base with foreign capital. It’s an ambitious pursuit of what would be, if it works, a powerful prescription for the U.S. economy designed to provide tailwinds to U.S. companies, U.S. labor, and the U.S. economy.

There are some important implications for investors. First, history demonstrates that countries only escape from their debt burdens by outgrowing them. Though the U.S. has run consistent fiscal budget deficits since World War II, for two decades after the war, its debt to GDP ratio remained low because economic growth outpaced borrowing growth. The U.S. desperately needs to address its debt, which ballooned in the wake of Covid, especially if it hopes to be able to meet the promises it has made to seniors through the Social Security and Medicare programs. Economic growth is realistically the only way it can happen and 2% annually won’t be enough.

Second, if companies opt to invest in the U.S., it will mean a tighter labor market, which is supportive of inflation-adjusted wages and consumer spending, especially for lower income households that have been hammered by inflation. Third, if the foreign direct investment even remotely approaches the level Trump claims it will (he is, after all, the greatest hype man that has ever held office by a long shot), the inbound capital will push the U.S. dollar up, which will help push inflation and interest rates down. A stronger dollar may exacerbate the trade deficit temporarily, but significantly lower foreign trade barriers and a larger share of domestic consumption being supplied by domestic producers should offset that over time. Regardless, higher economic growth and lower inflation ultimately translate to faster household wealth creation. That would be good for U.S. equities, U.S. bonds, but not good for gold.

Although former Prime Minister Trudeau may not understand Trump’s actions, we see a logical, ambitious plan. It is merely an evolution of various industrial policies that the U.S. successfully employed over the last 40 years. Granted, the adjustment period will irritate the U.S. consumer. And you can bet that the majority of popular news and social media will push the doom and gloom narrative, which could further cloud consumer, small business, and investor sentiment, increasing the risk of a recession. But if foreign countries come to the negotiating table, and foreign companies commit to investing billions of dollars in the U.S., a smart public relations campaign should be able to highlight the wins and reverse poor sentiment.

Our optimism about his plan notwithstanding, until his policies start to bear fruit, consumer, business and investor sentiment is likely to deteriorate, which is why, given pollyannish earnings estimates and above-average equity valuations, we think caution is warranted. If Trump is right, the economic advance will last years, if not decades, and bottom-ticking the market will be immaterial. His policies are a dramatic shift from the “free trade” status quo, his antagonistic approach risks a devastating tit-for-tat trade war, and because of that, prudence requires patience. This is not a time, in our opinion, to be a hero.

2 comments

James Winokur

April 4, 2025 at 4:34 pm

Mark,

Well written and informative. An important piece of our economic future is not contemplated here. I have been asking others, “where is the full plan and calculations that combine trade policy (tariffs) and federal income tax policy? In public speeches by the President, people in his administration and pundits, two different motivations for this tariff plan have been cited. One possibility, as you write, is to force negotiations that could lower other country’s tariffs or prohibitions so more U.S. goods could be sold in those countries. We would expect that negotiation to lead to lowering import tariffs into the U.S. The other premise, as stated by the President, is to achieve high enough levels of revenue from tariffs that U.S. income tax policy could create large tax cuts. But where is the math? How much is the administration willing to lower tariffs in any negotiations that would allow for the expected tax cuts offset by increased tariff revenue? How and when can the administration or Congress propose tax cuts without knowing the expected increased revenue from tariffs? If large income tax cuts are proposed with the assumption tariff revenue will offset those cuts, what will happen if that tariff revenue does not materialize?

Mark Schumacher

April 11, 2025 at 11:21 am

Hi James, great to hear from you. You pose a great question, and not one that many are asking right now. I think we’re all still reeling from the clumsy application of this policy and haven’t gotten to this stage yet. I suspect that, even though Trump has linked the tariff revenues to the budget deficit, which necessarily includes income tax policy, in typical Trump fashion, the numbers he’s throwing around for tariff revenues, in the $300b – $600b annually range, are ludicrous. In reality, they may be in the hundreds of billions of dollars initially, if other countries opt to fight rather than negotiate, but his ultimate goal is to have companies, American and foreign, relocate their manufacturing operations here in the U.S., which would, over time, reduce that tariff number. Now of course, there would be an even larger tax revenue that would be collected at the company and individual level, but there is no way he’s going to generate anywhere close to $6 trillion over 10 years with these tariffs. Honestly, I’m not even sure why he tried to link them to the budget and tax policy. I think he just needs to focus on the goal of getting companies to locate here and talk about those numbers instead. I’m not sure if the “one big, beautiful bill” includes any assumptions for tax revenues raised from companies locating operations here. I haven’t read the proposals that closely, and I’m not even sure, based on what I have read, that there are really any details in the bill as it’s currently drafted anyway. Seems like they’ll pass it and then figure it all out later. Which checks out. It’s the government after all.